In an age of rising ticket prices and competition from free digital media, keeping theatre accessible is a growing concern. But while ticketing schemes might get audiences in the door, it’s relaxed performances and audio description (among other methods) that truly make theatre open and available to all. In this guest blog, PIGDOG co-founder Max Barton discusses the theatrical power of accessibility and how his current production of Karagula by Philip Ridley champions the Extra-Live.

The unexpected things that can come from a performance where everyone is welcome.

I’ve borrowed this line from TourettesHero’s international hit Backstage in Biscuit Land, which centres on creator/performer Jess Thom’s experiences as an artist and woman with Tourette’s Syndrome. The full line goes something like this:

‘It was such a profound and beautiful thing that she shared with us and in stark contrast to the reactions you might expect of an audience. It was a demonstration of the unexpected things that can come from a performance where everyone is welcome.’

Spoken by Jess Mabel Jones as Chopin, the line refers to a relaxed performance of OneOfUs and Improbable’s x-rated Beauty and the Beast at the Young Vic, in which Jones was a puppeteer. Thom was in attendance at this performance, and she happened to keep repeating one particular tic—the name ‘Alan’. Another woman in the audience, as chance would have it, had lost the love of her life a year or so before and—I guess you can see what’s coming—his name was also Alan. If you saw Beauty and the Beast, you’ll know that at its heart was pure unadulterated love, and on the outside it was fucking sexy—essentially, it was theatre’s version of a romantic meal and a shag. And this woman in the audience had the unique experience of hearing her late partner’s name projected on top of all that, and as a result, she felt as if Alan was there with her, giving her permission to go out and love again.

I am one of the throng of directors who, in pursuit of *insert hyperbolic adjective* new forms, found themselves traipsing around Europe (often Berlin) for inspiration. Pinning down what defines a production as ‘European-influenced’ is best left to others in much longer articles, but I think it’s fairly uncontroversial to say one feature is a certain ‘auteurism’: a director or group of theatre makers using visual/musical/textual juxtapositions to make a strong personal statement. This can be through projections, microphones and post-modern anachronism, or by stripping something back until it represents that artist’s unique take on the text in its purest form. And it’s safe to say it probably won’t be kitchen sink naturalism.

My particular journey down the European path convinced me that I couldn’t comfortably draw influence from work I saw abroad by borrowing tropes or absorbing their aesthetic. My experiences in Berlin, in particular, have felt deeply and truly rooted within the politics and culture of that city. When I go to Berlin’s theatres, I am getting the city’s history packaged within the narrative form itself. On the other hand, I find British productions straying too close to that style empty and shallow, however impressive.

Because of this, I’ve been looking for ways to put my own cultural history on stage instead. (So far so wanky.) But here’s the thing: Ironically, it feels like the secret of making work that achieves these lofty heights is to make it as accessible as you possibly fucking can.

Andrew Haydon’s review of Blood Wedding by Graeae Theatre Company, whose work specifically champions deaf and disabled artists, is a case in point. Haydon writes:

Because of their status as “a disabled company”, [Graeae Theatre Company’s] default way of treating a stage–incorporating surtitles and signing for the deaf and plentiful audio-description for the blind *as a matter of course*–means that at any given moment about three languages are being used simultaneously. As an approach it simply makes all of us *read* the stage more carefully. As a result, it effortlessly aces the kind of stage semiotics that some “visual theatre” companies are still struggling with after more than a decade.’

It doesn’t takes much of a leap to attribute the same analysis to the juxtaposition of the Beauty and the Beast moment described in Backstage in Biscuit Land. And this multi-layered experience can be found at almost any Graeae show. I also had a similar experience at Soho Theatre’s fantastic Wendy Hoose, which featured hilariously integrated audio descriptions and captions, as well as at several relaxed performances.

For those who haven’t encountered relaxed shows before, here’s Jess Thom’s definition: ‘Relaxed performances extend a warm welcome to anyone who might find it difficult to follow the usual conventions of theatre etiquette.’

A true relaxed performance would normally include house lights being slightly up, sound design turned down a touch and an offshoot space for audience members who might need to leave. This isn’t always achievable—ironically enough, the show I’m about to shamelessly plug doesn’t have an environment safe enough to offer all these things.

However, an ever-increasingly large group of people are championing an idea inspired by these shows, called the Extra-Live Movement. Seeing that relaxed performances often provide exciting and particularly live atmospheres, the Extra-Live philosophy is based on relaxing attitudes toward theatre etiquette and re-emphasising theatre’s ability to respond directly to its audiences, which could—in addition to the obvious access benefits—break down social boundaries, interest younger audiences and compete with TV and film.

My company PIGDOG is among many who have committed to making all their performances Extra-Live. Along with pursuing far greater social, racial, gender and disability diversity within our creative teams, this has been a big part of our journey toward finding a theatrical form that reflects the London we know and love.

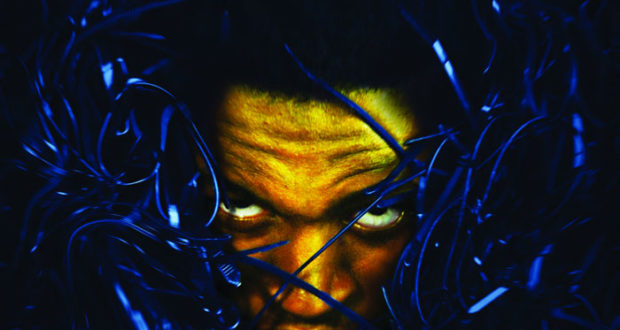

For our show Karagula, we’re also lucky enough to team up with one of the most groundbreaking writers London has to offer, Philip Ridley, who shares our vision for a truly diverse, accessible theatre. All performances of the show are Extra-Live and the cast and creative team reflect London’s extraordinary diversity. The variety of age, background, race and disability amongst the team has generated an electric atmosphere throughout the process, and I cannot wait to see the unexpected things that might happen at every performance of Ridley’s breathtaking play.

Karagula is playing at The Styx through 9 July 2016.

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond