Two years ago Lizzie Conrad Hughes read a book called “The Secrets of Acting Shakespeare” by Patrick Tucker, and “her head exploded”! In this guest blog, she explains why the method that Tucker expounded, of performing Shakespeare’s text from cue scripts (that’s just your own lines and a two word cue) so fired her imagination.

For years, my academic training in English literature had been flirting with my theatre experience. This was the moment their child was born: the work that we at The Salon Collective call Shakespeare:Direct.

We have been working with an ever-expanding group of actors, to discover and develop the skills of the Early Modern players who were performing the plays in Shakespeare’s own time. What seems like a leap of faith to us was basically second nature to them.

No actor is allow to read the whole text of the play

In the cue script approach no actor is allowed to read the whole text of the play. And for our upcoming performance of Two Gentlemen of Verona, nobody has (so far as I know). There’s no looking up vocabulary either, in case of accidental spoilers. Instead, actors are given one-to-one text coaching or ‘verse-nursing’, based on the recorded practice of Early Modern and Restoration theatre.

It is, in fact, perfectly possible to craft a character just from their own lines and their cues; if it weren’t, the thriving Tudor playhouse would never have existed. Back then, rehearsal was an unaffordable luxury as were ink, paper and the risk of plagiarism that came with having full scripts in circulation. The cue script method keeps you right on your toes, as the words are all you have to work from. You can only plan up to a point and you must, must listen in performance.

Performing is always electric. Nobody ever knows who they are performing with until the day. Many scenes I feel I’ve seen for the first time in these performances, no matter how well I knew the plays. As an actor, you have to be completely 3D in your decisions; there is no external director to shape you, only the internal one: Will Shakespeare himself. And nobody cares a fig if you call for a line from the book-holder. It makes not one shred of difference to the performance, or the audience. The fundamental principle behind this acting is trust: trust the playwright to give you what you need, trust your fellow players to work it with you.

Often, cue scripts show up utterly unexpected things.

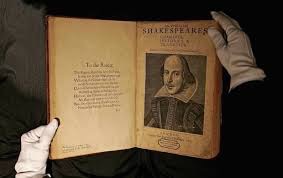

For cue script performance we use the First Folio of Shakespeare’s work, which is untouched by the editing of subsequent generations. Often, cue scripts show up utterly unexpected things. I’d never realised Malvolio made jokes until I looked as his part as a cue script. There they were, large as life. Love it! And there are repeated cues occasionally, which creates interruptions on stage; something completely lost in the contemporary approach to the text.

So how do you get directed by the text? Delightfully, the things that make the First Folio text “unreliable” to the modern reader (its funny spellings, odd punctuation and apparently-random capital letters) are the things that direct the player. I’ll try to explain.

Give the actor a problem when the character has one and you get instant acting for free.

Shakespeare’s verse structure is well known; all school children will hide at the words “iambic pentameter”. For actors, it’s an acting tool, an indication of how the character is feeling. If you accept that the rhythm of a person’s speech is affected by their emotional state, then this works well. So if a ten syllable line indicates a character is “normal” or basically OK, then elevens and twelves (even the occasional thirteen) show us more active emotions, stronger opinions.

Any lapse into prose suggests a change of attitude, or a change of tactic. If you have nothing but prose? You’re probably a servant, or not well-educated, or just very relaxed (as in Much Ado, a play with high status characters, but mostly in prose until the emotional chips are down). Meter also indicates significant words in a line, again suggesting character and personality (from words come opinion, from opinion comes personality). It is always very exciting to find clues in a line that force you against the meter: give the actor a problem when the character has one and you get instant acting for free. Genius, and really simple.

You always know if a comma or full stop is unnecessary if you begin by obeying it.

I know that debate rages regarding how much attention should be paid to Shakespeare’s punctuation, and rightly so, but it is still a valuable source. The idea that we could ever have exactly what Shakespeare wrote is impossible; but why automatically discard it?

We first assume each point of punctuation is correct. You always know if a comma or full stop is misplaced or unnecessary if you begin by obeying it. At the very least it’s a nudge towards what the words sounded like in performance; at the most, it is what the writer imagined when writing.

As with the funny spellings and funky punctuation, seemingly random capitals have typically been “corrected”. Again, we follow the principle that they may be deliberate, lending greater importance to the words they begin, and again leading us towards opinion and personality. I miss them in edited texts, they’re seriously helpful to an actor.

There are many more things I could mention that direct us in the text, but I’m out of space now. I have no idea if what we are ending up with is “what Shakespeare intended”, but I do know that it works, and it’s thrilling stuff.

Two Gentlemen of Verona is at Cockpit Theatre on 13th December 2015 at 12.30pm

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond