An exceptional performance brings Beckett’s peculiar trio of novels to the stage: immensely humorous and profoundly human.Summary

Rating

Excellent

Samuel Beckett’s work is not for everyone. Let’s face it, it is often absurd and can take a little work to grasp. But this production from Gare St Lazare does its damnedest to make it accessible, revelling in the immense humour and profound humanity of Beckett’s writing through an exceptional solo performance from Conor Lovett.

The trilogy are adaptations of three novels: Molloy, Malone Dies & The Unnamable, written about the same time as Waiting for Godot, and intended to be read rather than staged. Under the precision direction of Judy Hegarty Lovett, Lovett brings them blisteringly to life, meticulously grappling with a multitude of tensions, certainties and uncertainties to movingly articulate their sense in more than just words.

As Molloy begins, the character joins us from the audience. He’s one of us. He’s a man trying to tell his story but tripping from experience to experience, in an almost stream of consciousness fashion and where his control is questionable. We visit his mother, see him arrested for resting inappropriately on his bicycle, before running over and killing a dog. There’s a constant sense of absurdity, shifting realities as Molloy forgets words, or where he’s going. The narrative journey is uncertain, varied and unpredictable, like life itself. The only certainty is Molloy, who remains tangible and fascinating throughout.

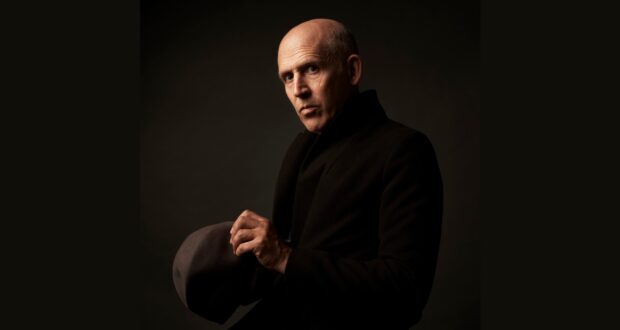

Lovett’s storytelling is magnificent, crafting hilarious characterisation within impeccable timing. We’re initially shown a kind of everyman in a plain coat (or is it two coats? Nothing is straightforward here!), but he subsequently displays moments of theatrical statuesqueness that give grandeur and gravitas to the struggling character’s strained existential deliberation. Lovett creates piercing dramatic tensions, holding them with supreme confidence. Understanding (and confusion) are communicated not only through spoken language but through the taut spaces in between speaking. We learn much about Molloy from what is unsaid, as questions are put and not answered, situations described but not explained.

In Malone Dies, a visually similar man appears, but now wearing an odd hat. We learn he is on his deathbed, relating his own story, but also inventing new ones, culminating in an imagined almighty bloodbath. Again, the narrative is confusing, but here focuses quite intimately on the detail of one individual contemplating lives as lived and how they might be, describing existential uncertainty.

Come The Unnamable, our character’s ability to tell his tale almost fails entirely. Words and ideas flow relentlessly around, making sense in context more than through structure; enacting the iconic realisation of “I can’t go on, I must go on, I’ll go on.” Throughout this piece an enormous shadow is cast on the backdrop, giving stature and illusory substance to a man who questions his life in fractured phrases, barely able to form sentences. He is ultimately diminished, his shadow shrinking as he leaves the stage. The lighting design throughout, by Simon Bennison assisted by Jonathan Chan, is impressive, fluctuating from subtle to striking; defining spaces where Lovett is utterly human, or immensely theatrical. Each abrupt exit backstage leaves a light which becomes an entrance for the next, giving a sense of inexorable cyclicality.

Beckett’s writing is ironic, funny and inspired as the language ranges madly from the obscure to the obscene, the lyrical to the intellectual: it encompasses all human possibility. There’s an underlying challenge of an authoritarian system gaslighting the everyman, and he throws out moments of startlingly poignant, wise revelation from unlikely characters, such as Molloy’s “Can it be we are not free? It might be worth looking into”. Bringing such iconic text from page to stage via this extraordinary, marathon performance gives it a viscerally engaging quality that is truly remarkable.

Written by Samuel Beckett

Directed and Designed by: Judy Hegarty Lovett

Lighting design by: Simon Bennison

Assistant Lighting Design by: Jonathan Chan

Produced by: Maura O’Keeffe

This event is now finished. You can read more about Gare St Lazare here.

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond