In an age governed by the ever-growing blogosphere, are the curtains closing on the reign of the critic? Rahul Rose and Eva de Valk review the situation.

Blog vs Critic

Words: Rahul Rose

On rare occasions in human history a technological shift will uproot the established order. The move from hunting and gathering to farming, the invention of paper in China and the introduction of printing in Europe each birthed a new world. Now a digital revolution is afoot and its chief agent is the Internet.

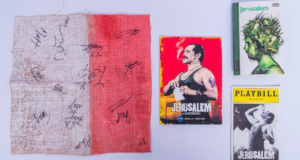

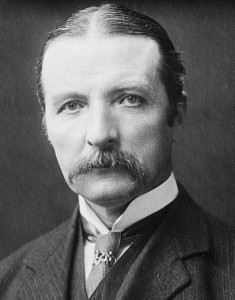

For hundreds of years, since the introduction of daily newspapers in the 18th century, the job of “the critic” remained largely unchanged in Britain. Critics were informed individuals, versed in the history of theatre. They were likely Oxbridge educated, white and male. Many saw themselves as arbiters of taste whose task was to answer the question: what is ‘good’ art? Their pleasure was supposedly distinct from that of the masses, a sentiment embodied by William Archer, the famed Victorian drama sage, who often lamented that in London: “there is not a single theatre that is even nominally exempt from the dictation of the crowd.”

Many saw themselves as arbiters of taste whose task was to answer the question: what is ‘good’ art?

Victorian theatre critic William Archer

Source: Wikipedia Commons

With the coming of the Internet this elite theatre critic is disappearing. The professional critic, who has spent years refining an informed subjectivity, is being usurped by the upstart citizen commentator.

These bedroom theatre critics are the precise opposite of their aging, professional predecessors. They are, for a start, more diverse. The Internet is open to all: black and white, gay or straight. And instead of one-way dissemination, from discerning critic to the silent masses, theatre criticism is now an opportunity for audience dialogue en masse. Blogs, YouTube, Twitter and countless other platforms mean anyone can publish – criticism has in essence become democratised.

The critic must now answer a new question to be relevant: “Should I, the consumer, spend my time on this?”

The Internet has revolutionised how entertainment is consumed and, in doing so, recast the very role of the theatre critic. We now have almost unlimited amusement at our fingertips. By clicking a button we can download an entire library of French New Wave cinema, listen to Malian rock music, or book tickets to see any one of the countless actors, dancers or singers who grace London’s stages each night. With so much fun only a click away the consumer is weighed down by the burden of choice. The critic must now answer a new question to be relevant: “Should I, the consumer, spend my time on this?” Star ratings, comments about ticket price affordability and assessments of the pleasantness of the theatre bar, all mainstays of online theatre blogs, are designed to advise the consumer on how best to spend their time and money. The old critic’s question: “What is good art?” barely gets a look in.

This is perhaps unfortunate, and it points to the loss associated with the decline of the paid critic – their learned and informed subjectivity is a necessary antidote to the relativism of the Internet. But such loss is small, especially when compared to the large gains. The unregulated anarchy of the Internet has allowed for a more diverse and democratic critic who better reflects the multicultural and variegated makeup of London, and indeed the world. More people are talking and writing about theatre than at any other time in history. Contrary to the pessimistic prophecies of doom and gloom, theatre criticism has never been in ruder health.

Verdict: The critic is more alive and relevant than ever – it’s just a different critic to the one most of us are used to.

Critic vs Consumer

Words: Eva de Valk

The debate about the necessity of theatre criticism is not a new one. More and more frequently, publications are cutting down on their reviewers and theatre coverage. Are we, then, slowly but surely moving towards a culture where mainstream coverage of theatre or other arts is simply not relevant anymore?

To answer this question we first have to look at another discussion: what is the role and responsibility of the critic? As I see it, the critic, on one hand caters, to the general public, and on the other to the practitioners, academics and other professionals working in theatre.

Within the theatre world itself the critic is without doubt very useful. By writing about new work they give exposure to new companies. They help build the historical record that for theatre, being fleeting in nature, is more difficult to maintain than, for example, for architecture or painting. And, most importantly, fair and balanced criticism can help artists sharpen their work, and challenges the pretentious and the lazy.

The critic on one hand caters to the general public, and on the other to the practitioners, academics and other professionals working in theatre.

But is the critic still useful to the ‘average theatregoer’? One of the most prominent aims of mainstream theatre coverage is to advise the consumer on what is and what’s not worth seeing. But the critic is in many ways just another person with just another opinion, and the chances of that opinion being the same or even similar to those of every other person who has seen a show are zero. I may tell you that I didn’t like the latest re-imagining of Romeo and Juliet, but who’s to say that that means you won’t like it either? Beauty, after all, is in the eye of the beholder, and my being critical of a show could discourage you from seeing a production you’d love.

Finding your own point of view is difficult if you let the critic tell you what they think you should see.

Apart from giving an opinion, the critic also analyses the performance to a certain extent. While knowing what you’re getting yourself into can certainly be helpful, it can take away the fun of interpreting what you’ve seen. Finding your own point of view is difficult if you let the critic (or the programme, for that matter) tell you what they think you should see. Of course, that doesn’t mean you won’t have an enjoyable evening. It will just make the after-show discussion with your friends a bit boring.

While the arguments above speak against the necessity, even the desirability, of theatre criticism for the general public, at the same time I don’t see how we can get by without it. Now more than ever, the offer seems almost unlimited, while our time and money are definitely not. So when we make the decision to spend these by going to the theatre, we want it to be worth our while. And that makes the critic, as a source for consumer advice, very necessary indeed; who would take the risk on an expensive performance they know nothing about if they could spend their money in a restaurant that has four stars on Yelp instead?

Verdict: Criticism may have its flaws, but at least it gets people into the theatre. And as far as I’m concerned, that outweighs everything else.

What do you think? Agree or disagree with Rahul and / or Eva? Feel free to leave your comments below!

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond