Most of us have probably been there: you go to see a show that’s slightly out of your usual range, and about ten minutes in you realise you have no idea what’s going on. You vaguely hope it’ll get better, especially since you have another hour and a half to get through. It doesn’t. Crap.

It’s the tricky issue of how much you could, should and want to know about a production before you see it in the theatre. Obviously, every audience member arrives with different baggage, in the sense of what they already know about the play, the context, the author, the director, and so on. This backpack of prior knowledge has a lot of influence on how they see the show. It’s no surprise that a seasoned theatregoer who has already seen many other productions of a particular play will have a different experience of that show from the person sitting next to them, who had never even heard of the play before they got roped into being a last minute ‘plus one’.

When you see a play, your understanding of it works on different levels.

When you see a play, your understanding of it works on different levels. Let’s start with the basics: the plot. If you don’t get the storyline of a show, it’s unlikely that you’re going to enjoy yourself very much. The importance of the plot is, however, dependent on the genre. In straight plays it’s usually a pretty big deal, whereas in dance, for example, it’s often less influential than the choreography. When seeing a ballet I personally like to read a quick Wikipedia summary on the way to the theatre; it allows me to focus on the dancing instead of trying to figure out what’s going on (which, with the lack of talking and all that, can be rather difficult). On the other hand, if I’m seeing new writing I most certainly do not want to know what’s going to happen. So in this case, a lack of prior knowledge can actually add to the overall enjoyment.

One step above the plot, we’re talking about the finer details of a production, things like references and jokes. These frequently point towards the overarching themes of the show or clarify the context in which it should be understood. It’s not necessary to understand all, or even any, of these, because you’ll still be able to follow the plot without them. But they definitely add depth, complexity and often humour to a show, so if you do get them you’ll probably get a lot more out of the experience. Here, then, having prior knowledge can certainly contribute to your enjoyment and understanding of a show.

Some theatre makers feel they need to explain themselves in the programme, others will let you make up your own mind.

And now we get to the last and most difficult level of understanding: the artistic intention. Playwrights and directors don’t just put stuff on stage because it looks nice or sounds good; they have a reason for doing it the way they do it. They want to tell their audience something, pose a question or perhaps encourage reflection on a certain subject. Artistic intentions come in all shapes and sizes, from the plain and simple to the mind-bogglingly complicated. Some theatre makers feel they need to explain themselves in the programme, others will let you make up your own mind. While there’s a lot to be said for the latter approach, ‘getting’ the intention behind a show can be difficult if you come in with a completely blank slate. I once saw a production of Macbeth where the director had decided Macbeth was suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and that many of the supporting characters were actually voices in his head. It was a brilliant idea, except that you almost needed a line-by-line knowledge of the play text to recognise which lines belonged to Macbeth, and which ones would normally have been spoken by other actors. Since, on principle, I never read a programme before a show, I spent most of the play being confused about why the story was so different from how I remembered it, and why the cast was so tiny!

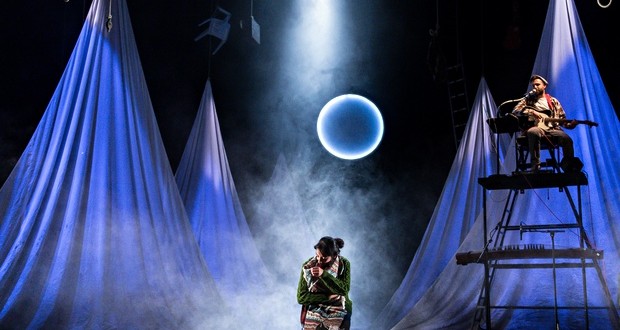

As a regular theatregoer I am keen to understand how theatre-makers strike the balance between challenging their audiences and making the work intelligible. I spoke to Amy Leach, director of the daring production of Brecht’s complex, socialist play The Caucasian Chalk Circle that recently played to teenage audiences at the Unicorn Theatre.

I don’t think an audience should need to know anything about what they’re about to watch.

ET: When working on a show, do you make any assumptions about the ‘average’ audience member, and what he or she may know about the subject and context of the play?

AL: I see myself as a storyteller, and I believe that every one in the creative team is there to serve the story and to make it as clear as possible. Whilst I would never wish to patronise an audience and ‘spell things out’, I try not to assume an audience knows anything about the play they’re going to see. I also don’t think an audience should need to know anything about what they’re about to watch – to have read the text or studied the theory and context behind it. I think that if that’s required, you end up with theatre that’s elitist and academic.

In a way, I hope our audience haven’t read the play beforehand; it’s a really hard play to read on the page.

ET: Still, The Caucasian Chalk Circle discusses complicated topics, like power and capitalism. Don’t you feel that audiences get more out of the play if they are familiar with the context?

AL: As you rightly point out, The Caucasian Chalk Circle is a particularly complicated play which is heavily rooted in the context it was written. Designer Hayley Grindle and I really struggled to understand all of it in our prep for the production – what the social hierarchy was, what the time scale was, how we should feel about each of the characters. But we saw our inability to understand it as a good thing. If we could make sense of it and answer these questions, then we’d also be able to communicate the answers clearly to an audience. I said to the actors on the first day of rehearsals that our most important task was to make the story as clear as possible. This was partly knowing that a large chunk of our audience would be teenagers coming to Brecht, and maybe the theatre, for the first time. But I also know that there are plenty of adults who don’t fully understand Brecht and so I didn’t really keep the age of the audience in mind – I just tried to make a production that I would understand if I was coming as an audience member. In a way, I hope our audience haven’t read the play beforehand; it’s a really hard play to read on the page. But I hope our production is vibrant and visceral enough that it grabs attention and takes our audience on the theatrical rollercoaster ride that I believe was Brecht’s intention. Then if it prompts our audience to go away and ask – who was Brecht? what were his intentions? – with our production as the catalyst, that would be great.

ET: And do you think a show can still be a success if the audience doesn’t get your intention behind the play or interprets it in a completely different way?

AL: Absolutely. That’s the wonderful thing about the arts – there is no ‘right’ answer.

So there you have it: the question of how much prior knowledge is ideal for the theatregoer is simply unanswerable. The best way to go about it is probably to figure out what works for you personally. If you usually avoid summaries and reviews like the plague, why not try reading some beforehand. And if you normally come armed with programmes and extensive background information, let the show surprise you for a change. Who knows, it might open your eyes to entirely new ways of enjoying theatre.

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond

Everything Theatre Reviews, interviews and news for theatre lovers, London and beyond

Hmmm this is something I muse on a lot, so thank you for this considered and questioning article. I agree it is subjective and depends on the production. There is another level of prior knowledge I think, which is to do with how ‘artsy’ you are and how many similar productions you’ve been to. I remember coming out of a show by the extraordinary drag performance artist Ivo Dimchev at In Between Time Festival several years ago, during which he draws a syringe of his own blood from his arm and then auctions it to the audience. I came out saying “WOW I HAVE NEVER SEEN ANYTHING LIKE THAT BEFORE” …of course for all the hardened performance artist junkies in the audience, a bit of blood onstage was nothing, so our experiences were very different! I still think that was a very special show but if I watched it now, being more familiar with that kind of boundary pushing performance, I would probably be less struck by it. For this reason I think that often, ignorance is bliss and going into a show blind is likely to give you the most immediate and ‘real’ experience of the show, as the theatre maker wanted you to experience it. It is good to leave prior knowledge and preconceptions at the door in my opinion!